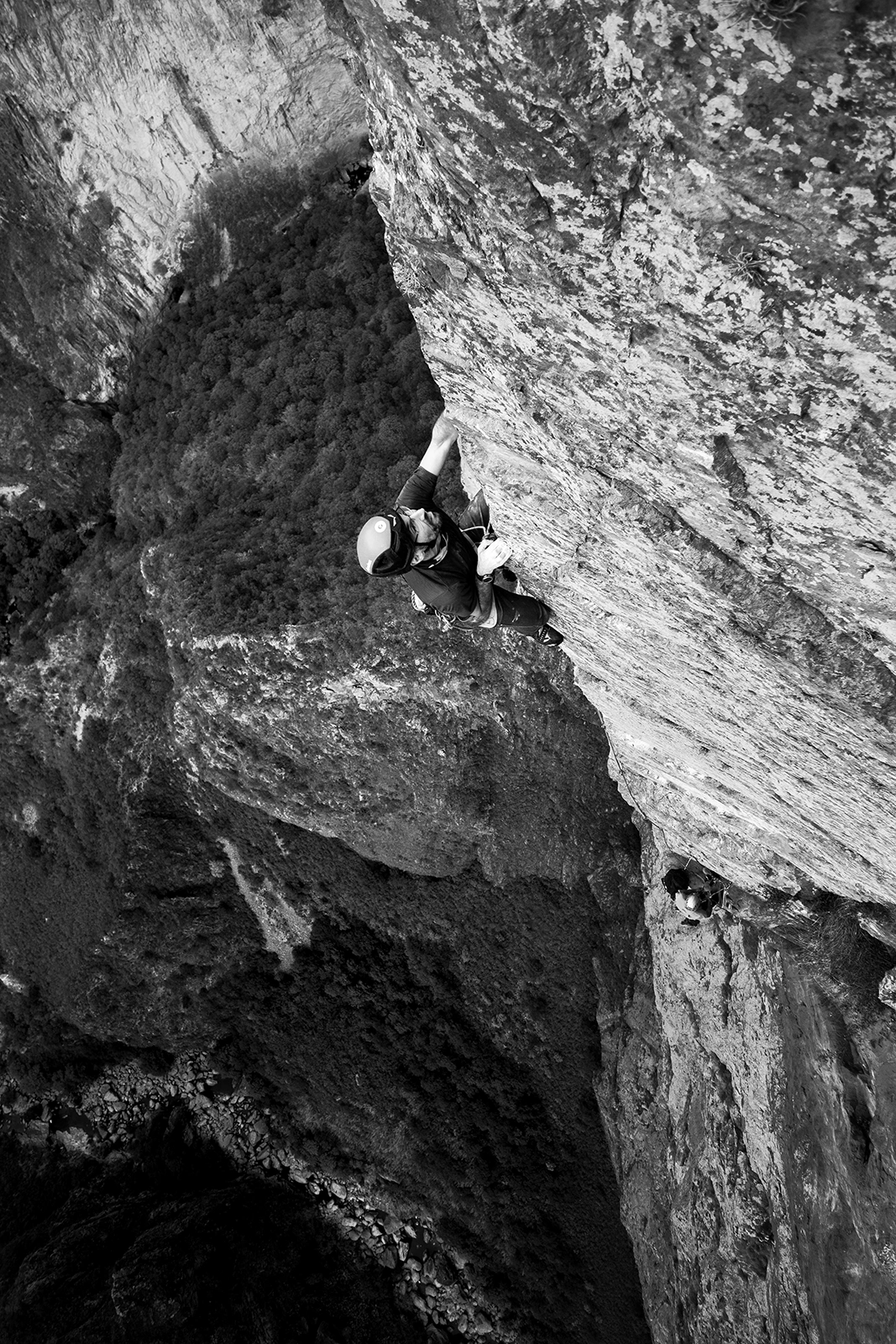

EL GIGANTE, Via Logical Progression

CANYON CANDAMEÑA, Sierra Tarahumara, Chihuahua, Mexico

Date: 2 November 2023

Climbers: Fabrizio Della Rossa, Thomas Gianola, Lorenzo Gadda

Report and story written by: Fabrizio Della Rossa

GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS OF THE ROUTE:

The route has 27 pitches. The grading is accurate, rather strict. In particular, even the pitches below 7a should not be underestimated as they may hold unpleasant surprises. The climbing is very varied: many technical vertical walls, overhangs, holes, and cracks are present. The on-sight difficulty may be increased by the lack of magnesium marks. The distance between the bolts varies: almost sport climbing-like on the 7c-c+, on other pitches it can reach up to 6 meters, very often 3-5 meters. The route was bolted by different people from above, so there are also differences between pitches and sometimes long run-outs even on the hard sections. That said, the overall evaluation of the bolting is more than good. The beauty of the climb is exceptional and the vegetation hardly ever bothers.

STRATEGY:

Day 1: trekking to the top, bivouac at the top

Day 2: rappelling down about 5 hours, climbing the first 10 pitches, bivouac at the end of L8

Day 3: climbing up to L19, bivouac at the start of L19

Day 4: climbing to the top, return

We left 1 haul bag on top, 1 haul bag at bivy 2, and 1 haul bag at bivy 1. The first 8 pitches climbed with 1 small backpack.

4×4 transport needed

The Mexican phone starts getting signal a few pitches from the top

Useful local contacts: Rancho San Lorenzo: Ana Gabriela Dominguez Olivas +525554598288

MATERIAL:

Rope team of 3 people, material used:

- 2 half ropes of 60 meters

- 1 retrieval cord of 5 mm by 50 meters

- a 40 meters static rope

- 20 quickdraws

- friends from 0.2 to 2 (little used)

- 2 jumars and 2 microtractions

- some locking carabiners and slings

- three haul bags, one of which was left on top

- 1 small backpack for the first 8 pitches

BIVOUACS:

- 3 sleeping bags comfort 5/0

- inflatable mats

- 1 hammock

- 35 liters of water

- jetboil (cartridges can be found in Chihuahua)

CLIMBING GUIDE:

Guia de escalada en México by Oriol Anglada

Preparation: equipment, strategies and Don Fernando

It feels like being in a Western movie, now with few horses and no “caballeros”: here, nature stands powerful and wild, giving a sense of an ancestral state where man and his artifacts are so tiny and merely sketched that they are swallowed up in the vastness of the landscape. The day after our arrival in Basaseachi, we go up with an old GMC truck to a lookout over the Canyon network: difficult dirt road, rugged, no railing or tourist board, just 4 wooden planks forming a shelter for narcos. This is how Don Fernando explains it: the satellite dish next to the shelter and the automatic rifle shells on the ground confirm his words. Don Fernando is an authority here: his 80 years can be guessed from his tired eyes in the evening, otherwise, he is someone capable of driving his GMC for hours on the worst dirt roads, captivating everyone with his chatter, discussing global geopolitical issues, and asking God for the fortune to live another 20 years to see a couple more projects he has in mind realized. What certainly helps is the presence of his wife, about forty years younger! In addition to the two of them, the permanent crew of the GMC consists of his grandson Pablo and the handyman Carlos. Of course, we three, who would then be the clients, also find a place in the back of the GMC.

Don Fernando, who was an airplane pilot and who could barely tolerate stays in the United States, always curious and informed, who owned a Cessna and a small runway in the middle of the Sierra, well, he is always driving while Rebecca keeps him company in front. Carlos and Pablo are in charge of opening and closing the gates for the cows. Don Fernando has black eyes and a bit of cataract; radiant white mustaches and a standard sombrero, a rounded belly from consuming chips and coca cola while he doesn’t like alcohol. Nor does he like living in the city, where he also has a house. He is happy in his isolated Ranch, in a house made of wood and lime, heated by wood stoves. Don Fernando sees a radiant future for his land, the Sierra Tarahumara: he talks about ecotourism, bike trails, climbing, and quad tracks: considering, perhaps, all that slice of the American and particularly Mexican market, that just can’t make it without an engine under their seat!

One day Don Fernando loads us up with the crew and takes us to visit another of his Ranches: we enter the jeep and the pines thin out, leaving space for a grassy plain with a small stream running through the center. The dry, yellow grass spreads out into the distance against long red walls. The pines resume up to the ranch’s cabins: behind the cabins and the restaurant, beyond the stream, the walls modulate the valley: yellow towers, gray slabs, and reddish overhangs. He tells us that these accommodations have been ready for several years but only now, due to some problems with the narcos, have they been able to open to tourists. Don Fernando, although he has never climbed, senses the potential and asks us what we think. After walking the few steps that separate us from the rocks, we confirm the potential that the excellent rock here represents for climbing.

From the rancho, in a few minutes by jeep, we arrive at the narcos’ lookout from where the tangle of canyons appears in all its powerful majesty. Completely bewildered we watch 1000 meters below the slow flow of the river, then farther on, beyond the succession of walls, the network of canyons seems to go on forever.

Don Fernando says this place is like the Grand Canyon when it gets big: this I don’t know, surely the Gringos’ canyon will be either longer, deeper or bigger, so much we know how much the Americans need to excel. What is certain is that, beyond the records, to me who cannot stop looking, in the light of a gentle autumn sunset, I seem to catch here the beginning of this planet of ours. If not the beginning, perhaps the end.

Approach to the start of Logical Progression

The summit of the Giant, from its southern side, rises a few meters above the pine forests of the plateau. Instead, toward the north it plummets 900 meters seamlessly into the abyss of Candamena Canyon. The first climbers of the wall employed mules, porters and machetes to pave the way to the bottom of the canyon. Nowadays the most convenient way down is to go through the top and from there rappel down the entire wall.

So set up, we load our big bags into Don Fernando’s jeep: full crew, in about two hours of bad dirt road we arrive within sight of the summit. From here the three of us climbers wave goodbye and, loading our heavy bags, we set off toward our destination.Upon reaching the summit we make an unplanned decision: instead of starting the doubles tonight, we set up a comfortable bivouac and, lighting a fire, enjoy a 5-star hotel night.

The following day, after 5 hours dedicated to the descent, we finally touch the bottom of the canyon: the river is not far away but the dense vegetation relegates us to a tiny space between the wall and the brambles.Having reached the base by rappelling from the top seems to me to have taken some sense out of an activity that already in itself doesn’t make much sense: now I wonder, why climb all this wall if then, having reached the top, we will be back where we started? In any case now, pressed against the wall, with ropes already spun to the ground, and water and provisions left along the wall, it seems decidedly late for philosophical reflections.